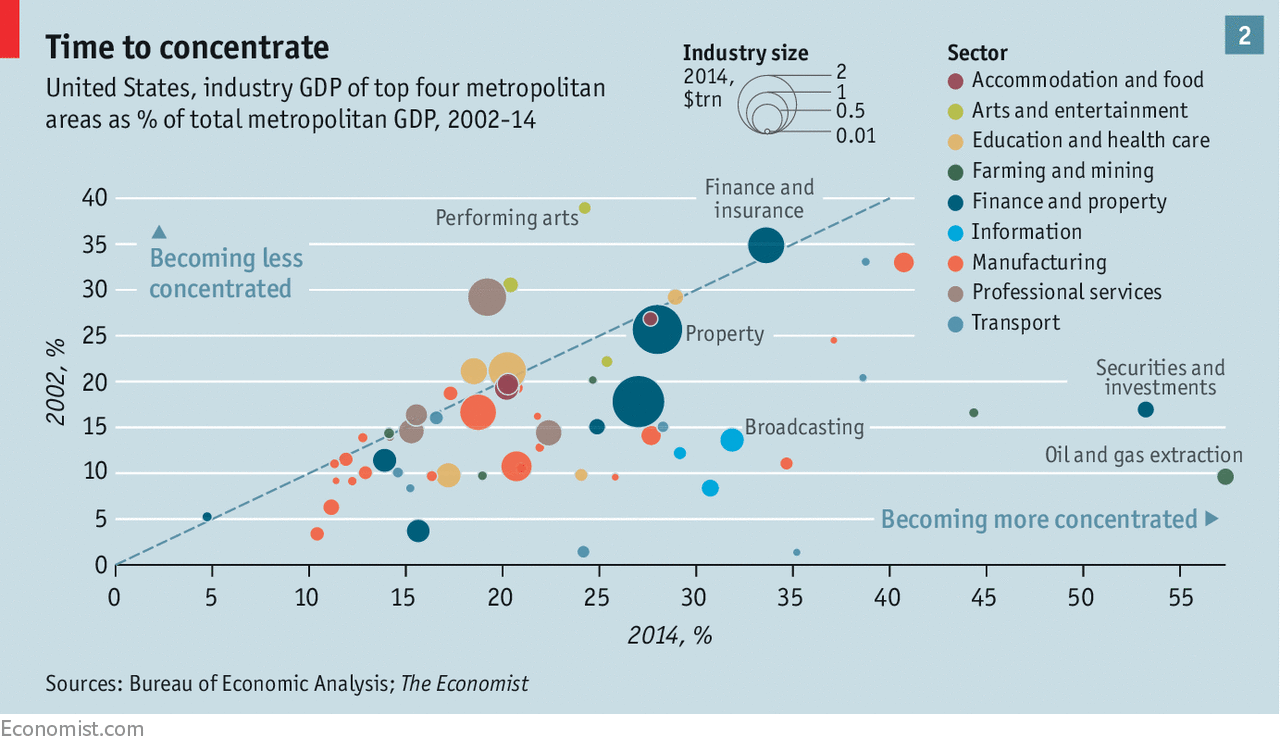

The Economist has a long and important article in the current issue called “Globalisation has marginalised many regions in the rich world” (now they tell us…). One of the interesting tidbits in a chart that illustrates increasing concentration among a vast array of industries. They track the share of GDP by industry being generated in the top four metro areas in 2002 and 2014 to show change in concentration overtime.

The dots aren’t all fully labeled and so we really don’t get the details behind his. The key is how many segments have become more concentrated versus less. Again, I’m reminded of former GE CEO Jack Welch, who saw this coming and famously said he only wanted to be in a business if he could be number one or number two. (Subsequently a number of industries rolled up into de facto “two towers” models: CVS and Walgreens, Home Depot and Loews, AT&T and Verizon, etc).

This is putting a lot of regions – the article highlights Scranton – in a serious pinch. There’s a lot in this article, so read the whole thing. Some additional highlights:

Between 1990 and 2010 the rate of economic convergence across American states slowed to less than half what it had been between 1880 and 1980. It has since fallen close to zero. Rich cities started pulling away from less well-off counterparts (see chart 1). According to the Brookings Institution, a think-tank, in the decade to 2015 productivity growth in American metropolitan areas was highest in the top 10% and the bottom 20% (where, by definition, the baseline was low). Struggling middle-income cities like Scranton fell further behind. A recent report by the OECD found that, in its mostly-rich members, the average productivity gap between the most productive 10% of regions and the bottom 75% widened by nearly 60% over the past 20 years.

….

When countries with lots of low-wage workers begin trading with richer economies, pay for similarly skilled workers converges. Those in poor economies grow richer while in rich countries workers get poorer. The effects are felt more in some places than others, and not only because the sort of people who lose out to trade tend to live in similar places. Globalisation did direct damage to many local and regional economies because of the way those regions work.

…

The past few decades have been good for the richest firms and places. They are as productive as ever; America’s slowing productivity is the result of increasingly poor performance by firms below the upper ranks. Across a wide range of industries the share of output generated by America’s top four metropolitan areas for each industry has risen, often substantially. In the financial industry their share of output rose from 18% to 29%, and in retail, wholesale and logistics from 15% to 21% between 2001 and 2014.

…

But it is a different story within borders. Diffusion of technology from top firms in one country to laggard firms in the same country has slowed down. The authors of the study reckon that a lack of interest in adapting technologies to local circumstances may account for part of this, suggesting that the more the best firms focus on a global (rather than domestic) market, the slower productivity-improving techniques and technologies spread locally. The rise of superstar firms means that fewer places are home to businesses operating at the productivity frontier and that domestic investment is lower than it should be. In less dynamic local markets, nonsuperstars seem neither willing nor able to adopt the best technology.

from Aaron M. Renn

http://www.urbanophile.com/2017/10/19/superstar-effect-everything-edition/

No comments:

Post a Comment