Eduardo Porter at the New York Times picks up on a theme I’ve hit repeatedly in this blog over the years, namely the challenges that smaller cities/regions face in trying to adapt to the post-industrial economy.

Eduardo Porter at the New York Times picks up on a theme I’ve hit repeatedly in this blog over the years, namely the challenges that smaller cities/regions face in trying to adapt to the post-industrial economy.

You don’t want to be hit by a recession in a city like Steubenville, Ohio.

Eight years into the economic recovery, there are thousands fewer jobs in the metropolitan area that joins Steubenville with Weirton, W.Va., than there were at the onset of the Great Recession. Hourly wages are lower than they were a decade ago. The labor force has shrunk by 14 percent.

The dismal performance is not surprising. Built on coal and steel, Steubenville and Weirton were ill suited to survive the transformations brought about by globalization and the information economy. They have been losing population since the 1980s.

But what made them such bad places to ride out a recession was not just their industrial mix. With only about 120,000 people, they were just too small to adapt to the shock. And they may be too small to survive.

Steubenville and Weirton are on the losing side of yet another cleavage dividing the haves from the have-nots across the United States: geographic inequality.

…

Some of the advantages of big-city living are not hard to find. For starters, big cities have a greater variety of employers and thus more job opportunities in a richer mix of industries than do small cities, whose fortunes are often tied to those of just a small number of employers.

Bigger cities are more productive. They are more innovative. They draw better-educated workers by offering them higher wages. They develop a richer variety of industries. It should not be surprising that they are growing faster.

You can see articles on a similar theme in the Wall Street Journal and the Economist.

Back in 2009 I laid out a heuristic I called the “Urbanophile Conjecture”: if you want to be a successful city in the Midwest, it helps to be a state capital with at least 500,000 people. This defined success based on above national average population growth. There were some exceptions but this was a useful rule of thumb.

In 2008 I talked about “minimum sufficient scale.” This is the idea that there are certain things, such as a major airport, for which a region has to have a minimum size scale to support on a viable basis. To the extent that these things are necessity to compete in the modern economy, if you’re too small to support them you’re in trouble, unless you’re a sufficiently short distance from a larger place that can.

In 2010 I laid out the concept of “shadow cities” – those that were always or rapidly reduced to branch plant status that lacked a strong indigenous based of export (from the local market) industries.

When you add all this together, in the Midwest and Northeastern Rust Belt it seems to be mostly metro areas of 1-1.5 million or more that are doing well. Smaller metros can thrive, but it generally takes a major special asset like a state capital, major university, or Fortune 500 HQ.

Those bigger cities have thicker labor markets, airports, amenities like pro-sports, lots of restaurants, a critical mass of talent, often major export businesses, and major institutional that give them a leg up in rebuilding. Smaller cities are often lacking in these

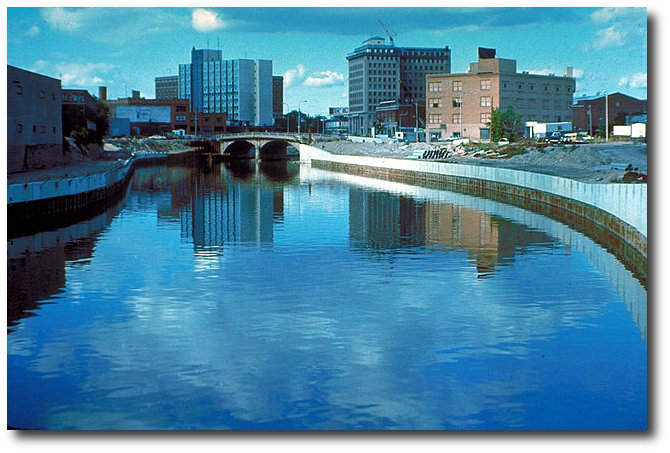

Contrast Detroit with Flint.

Detroit: 4+ million person region, one of nation’s foremost collections of engineering talent, many HQs and dominant North American location of the auto industry, major international airport, primary trade gateway to Canada, a full panoply of major metro assets (sports, arts, etc).

Flint: A sub-one million person region. Originally HQ of GM but reduced to branch plant status quickly. Much lower talent concentrations. Minor airport only. Far fewer major institutional or corporate assets. (There are some, but not enough).

This difference helps explain the divergent strategic conditions facing those environments. Flint is in a much higher degree of difficulty situation.

Thinking of the future of these smaller places is important to the future urban agenda. We’re not talking one or two minor places, but many cities the collectively still have many people – people who are our fellow citizens – living in them.

from Aaron M. Renn

http://www.urbanophile.com/2017/10/12/the-small-city-struggle/

No comments:

Post a Comment