Over the years I’d periodically see newspaper articles talking about sewer projects to eliminate something called “combined sewer overflows.”

Two things struck me about them. 1) How expensive these projects were (sometimes billions of dollars). 2) How little public discussion of them there was compared to say stadiums, convention centers, or new transit lines.

I wanted to correct that lack of attention, and wrote my new Manhattan Institute report “Wasted: How to Fix America’s Sewers” to give an accessible overview of what this combined sewer thing is all about, highlight the costs and particularly how low income households are affected, and identify strategies to help cities cope with the cost.

This is an area where I do believe additional outside aid to cities and sewer districts are needed. You may have read that Flint may have to find $1.5 billion to replace its lead water pipes. Nobody thinks Flint can come up with that kind of money on its own. But other cities are getting hit with bills of similar magnitude for sewer remediation with limited outside help.

The Flint situation also highlights that sewers are far from the only item in the liability stack these cities face. Drinking water is another huge area, as are streets, crumbling parks and buildings, and unfunded pensions. Cumulatively, this is a staggering burden falling on some of America’s most struggling municipalities.

Here’s an excerpt from my paper:

These huge sewer costs are, as noted, legally mandated by the federal government; localities have no choice but to spend the money. As Springfield, Ohio Mayor Warren Copeland complained: “This is the biggest, hugest unfunded mandate that I’ve ever seen in the time I’ve been in public life. Basically, the EPA at the federal level is prepared to tell us that we have to keep spending money and there’s no help from the feds to deal with it. It’s just a disaster from my point of view. There doesn’t seem to be any way out of it.” This means major rate increases. For its part, Springfield has sufficiently satisfied the EPA that it is not under a consent decree; but it is still spending big, proposing to raise sewer rates by 7 percent (well above the rate of inflation) each of the next three years to help fund the program.

The cumulative impact of these rate increases can be substantial. For example, in Providence, Rhode Island, the average sewer bill has gone from $130 annually in 1996 to $470 today, in part to pay for that city’s remediation program. If its Phase 3 plans are approved, household bills will rise to $670 by 2020—a 43 percent increase in just five years—with more to come.

Click through to read the entire report.

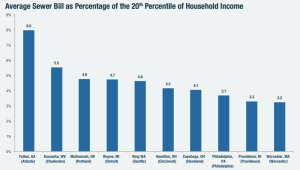

Here’s just one chart to give you a flavor of the cost. Jeff Rexhausen at the University of Cincinnati compared average sewer bills in the top 100 American counties to the household income at the 20th percentile. I took some of his data and put it into a chart:

This isn’t perfect. Lower income households do qualify for discounted bills in some places. But it illustrates that utility costs can loom large in low income household budgets. One thing a lot of these post-industrial cities have, alas, is a lot of low income households. Again, click through to read the whole report.

from Aaron M. Renn

http://www.urbanophile.com/2016/02/25/the-stunning-cost-of-federal-sewer-mandates/

No comments:

Post a Comment