Photo Credit: Jpatoka, CC BY-SA 3.0

I was talking with someone at dinner last night and he asked me what globalism was. I responded with four key elements:

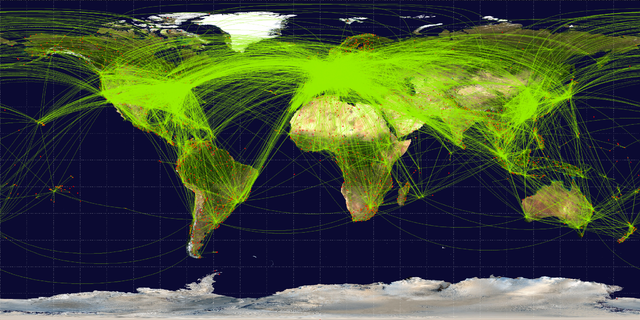

- Borderless World: A belief in the ever freer movement of goods, services, capital, and people around the globe.

- Global Culture and Regime: A shared set of social, lifestyle, and political norms, along with supranational institutions that embody them, that explicitly supersede all national norms and institutions.

- Flat Earth Morality: A belief that all people and entities are to make decisions are in a way that weights every human on planet earth equally, rather than expressing a higher obligation towards their neighbors, their own countrymen, etc.

- Neoliberal View of Personhood: An implicit belief underlying all of the above that human beings are in effect widgets, and can be viewed similarly to goods and services (as in point #1).

Few people, even avowed globalists, embrace these principles in their absolute form. But their thinking tends in this direction, and in all four dimensions their prescription for the future is always: “more”.

Borderless World

This is the most easy to understand plank in globalism. The explicit aim of governments has been to reduce barriers to trade, investment, and migration flows. This is what the WTO process is all about, for example. The European Union and its Schengen travel area are a great example of this kind of globalist project in its most advanced form. The idea is make Europe a lot more like the United States internally. Similar logic would extend this type of regime further and further as borders ultimately wither away.

Global Culture and Regime

Various streams of Western thought have tended towards universalism in their scope. Communism is one example. The US idea that its liberal values – spreading democracy around the globe and such – are universal human values is another.

We also see this in the emerging social culture of the Davoisie, which extends down to the level of the urban Millennial progressive. These values are now largely shared by the educated and moneyed elite globally, which is why the creative class of London, New York, Paris, Buenos Aires, and Munich can have more in common with each other than they do with their working class residents of their own country or even city.

And of course these values are embedded in institutions like the UN or European Union which speak in the name of the international community, the European community, etc.

It’s unlikely in my view that this will ever lead to a real global government. For all that the world’s elites have in common, as Michael Lind has pointed out, they are really a federation of national elites. This is why most Americans aren’t moving to Canada no matter who the president is.

I see this as similar to the ecumenical movement. Although it was broadly supported in principle, the mainline churches were never able to really merge, largely because of bureaucratic and status turf considerations. Similar conditions apply with national status and political hierarchies.

Flat Earth Morality

This is one people are somewhat schizo about, but it’s clearly a basis of argument on things like global trade, climate change, migration, etc. The idea is that national governments or actors need to make decisions that morally weight the needs of everyone on planet earth equally, regardless of their relationship.

For example, one justification of globalization is that it has lifted a billion people out of poverty in the developing world. This allows national leaders – invariably winners from globalization, I should point out – to morally justify their self-interested decision to harm their own fellow-countrymen by pointing to some offsetting global benefit.

Traditional human cultures are hierarchical in their conception of moral obligation. That is, our first obligation is to our family, then tribe, then nation, and finally to the world at large. Natural selection would suggest this is genetically hardwired into humanity. Hence again we see that people arguing for a flat schema of obligation are almost invariably attempting to justify something or a system that benefits them and theirs personally.

There are offsetting trends here, including the “buy local” movement. People tend to shift from a hierarchical to a flat schema of evaluation opportunistically.

Neoliberal View of Personhood

This is really more an underlying assumption of the three previous items than a separate point. They all implicitly see people as interchangeable widgets. It’s effectively blank slatism with one exception: the idea that people are homo economicus. That is, it views humans concerns as primarily economic, and assumes utility maximization, rational behavior, etc. are hard wired into people.

So with global trade, goods, services, and capital flow freely to the most economically efficient location. And people flow freely in a similar way. They are simply a factor of production, no different from a iron ore or bonds.

The flat moral schema also relies on seeing human beings as effectively a pile of widgets in a warehouse. They all have equal value under “mark to market” accounting. They also have no intrinsic relationship to one another. Hence there’s no reason to value one over the other. No do you need to know much about about any particular widget, just whether or not its economic value is rising or falling.

Globalism in the Real World

Other than the borderless world point, few people would explicitly conceptualize globalism this way. But many clearly do embody all four ways of thinking. I don’t know anyone who subscribes to them in a pure or absolute form. But as a directional thrust, most advocates of globalism would see at least the first three as a good thing and a moral advance. They are generally promoting more of all three.

The reasons for this are pretty obvious. Trade has in fact raised living standards of a billion poor people around the world. Migration has benefited elite sectors of the economy economically. Cooperative global or regional institutions did do a good job of bringing peace to Europe in the wake of two devastating wars. Driving around Europe without annoying passport controls is a joy. Decisions in one place can have global ramifications that should be considered.

It’s also the case that this is a bipartisan consensus. So globalism is not a product of the Democrats or Republicans, but of both. In Europe, virtually all mainstream parties of the left and right equally support it.

The main problem for globalism is point #4: human beings aren’t widgets, aren’t homo economicus, and don’t like being treated as such. And while the elite might aspire to flat earth morality, in the real world political communities are local and national – and still tribal in many places.

What we’re seeing right now is the conflict arising from these contradictions playing out. Whether advocates for globalism can resolve them in a manner consistent with their own stated values will tell the tale of how the world plays out in the future.

from Aaron M. Renn

http://www.urbanophile.com/2017/05/05/what-is-globalism/

No comments:

Post a Comment